Dream 18: The best 18 holes built in the last 44 years

Published in 1976, The World Atlas of Golf should be a cornerstone of any golf architecture library, and maybe its finest feature is contributing editor Pat Ward-Thomas’s article, “Elements of Greatness: A Classic Course.”

Remaining true to each actual hole number (a No. 1 had to stay a No. 1, a No. 2 a No. 2 and so on), Ward-Thomas created an ideal 18, picking one hole from famous courses worldwide.

“Many may disagree with the composition of the course,” he wrote, “but nobody could fairly dispute that it would call upon a golfer to demonstrate skill in every part of the game; that it embraces the quality of exceptional design, and much of the beauty with which golf is blessed; that it would command respect from the mighty and be a great deal of fun for anyone to play.”

Mission accomplished, and brilliantly so: Ward-Thomas rightly focused on the quality of each hole as well as how those holes would relate to one another. It was an eye-opening read the first time and remains just as entertaining the hundredth time. Still, the book was published back in 1976—what about all the brilliant layouts built since?

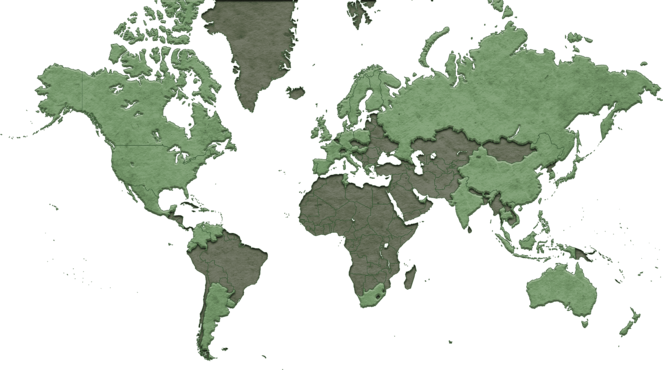

Many people, myself included, believe that we’re living in a second Golden Age of course design, so it seemed only fitting that my homage to “Elements of Greatness” stick to places built post-World Atlas of Golf. As it’s meant to be a celebration of modern design, this list is restricted to one entry per architect, to acknowledge as many leaders in the field as possible. Also worth noting: 14 of these 18 holes are accessible to the paying public, a telling sign of progress.

Hole No. 14: Chambers Bay

University Place, Wash. — Par 4, 495 Yards

Architects: Robert Trent Jones Jr. with Bruce Charlton and Jay Blasi

Why it’s great: A dogleg that tempts — as it should.

Overview: At the heart of great architecture lies the temptation to attempt something to gain an advantage for the next shot. The dogleg is among the most time-honored of the myriad ways to present such a puzzle, and this one is among the best.

From an elevated tee, the golfer can readily grasp the risks and rewards of hugging or even cutting off the dogleg by carrying as much of the sandy waste as possible. A small central hazard of the sort far too infrequently found in modern architecture must be avoided as the hole elbows from right to left. The golfer then faces a hugely appealing approach thanks to the fescue fairways, whereby a low bullet draw can run forever toward a bank along the green’s right that helps feed the ball toward the hole. A sprawling bunker complex runs tee to green along the left and exemplifies Robert Trent Jones Jr.’s artistry—no surprise from a man who takes pride in composing poetry.