What About Bobby?

In its CliffsNotes version, the story of American golf course architecture goes something like this: The field enjoyed a glorious run in its Golden Age of the early 1900s, only to lose its way after World War II, with excessively penal and overwrought designs, before finding itself once more in recent decades, when it learned to tread lightly on the land again.

If you’ve bought that script, Robert Trent Jones Jr. might like to have a word.

“It isn’t just an oversimplification,” Jones says. “It’s also factually incorrect.”

It’s an autumn afternoon at CordeValle, a rolling course he designed in the southern foothills of the Silicon Valley, and Jones is shuffling through the rough of a long par 4. At 83, wearing gray slacks and a mustard-colored sport coat, bushy eyebrows framing his cherubic face, he calls to mind a Hogwarts headmaster dressed for an Ivy League faculty lunch. In lieu of a golf club, he is carrying a cane, which he uses to point out features in the landscape.

“Look at the lacy filigree of that oak,” he says gesturing toward a tree with ancient tangled roots. “And see how the contouring behind the green mirrors the outline of the hills? I’m following Mother Nature’s lead, and I learned to do that from the best.”

When you’re hanging out with Jones, it helps to have a pocket Webster’s within reach (filigree: an ornamental work of fine wire formed into delicate tracery). Passing knowledge of Renaissance painting, iambic pentameter and environmental policy come in handy too. Jones is fond of holding forth on all of the above.

But his deepest expertise lies with a pursuit that was practically imprinted on him at birth. Like his younger brother, Rees, Jones—who goes by “Bobby”—is the son of Robert Trent Jones Sr., the Robert Moses of mid-20th-century golf course architecture, a towering figure whose original works and remodels on properties spanning from Peachtree and Spyglass Hill to Mauna Kea, Baltusrol, Congressional and beyond, helped define the game for a generation.

“I’m glad I brought this monster to its knees,” a weary Ben Hogan memorably said after winning the 1951 U.S. Open with a four-day total of seven over par at Jones Sr.’s redone version of Oakland Hills in Michigan. Among other hallmarks, his courses were notoriously tough.

Both Jones boys followed their father into the profession but branched out onto different paths. Working from the East Coast, Rees inherited his old man’s moniker as the Open Doctor, many of his headline projects being surgical procedures on big-time tournament courses. Bobby, meanwhile, got his father’s name but developed his own variable style, which, from his headquarters in California, he spread liberally overseas.

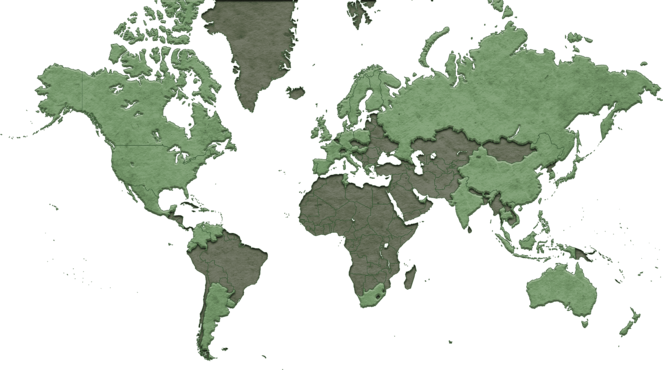

“The sun never sets on a Robert Trent Jones course,” the elder was fond of saying. The same is true of Bobby’s oeuvre. In the 50 years since he broke off from the family firm, hanging out his own shingle in Palo Alto, Jones has designed more than 200 courses of every genre, a portfolio that covers 45 countries and every continent but Antarctica. Domestically, he has hardly been hands off. Two of his best-known projects, CordeValle and Chambers Bay, have hosted majors; another, SentryWorld, in Wisconsin, where Jones recently updated his own work, will stage the U.S. Senior Open next year.

But in the eyes of many aficionados, some of Jones’ finest efforts are ahead-of-their-time designs in locales as distant as the coasts and bushland of Australia, largely out of sight and mind for the American market.

“Most golfers are aware of Chambers Bay, with its wide fairways and lavish bunkering schemes,” says Ran Morrissett, architecture editor for this magazine. “What people may not realize is that [Jones] was building equally artistic creations 20 years prior. In the early 1990s, few could compete with his artistic flair, and his designs stood out as originals.”

These are interesting days for Jones. At an age when he could be long retired, he is working with as much urgency as ever. With his own son, Trent, running business operations and a small team of associates at Jones’ side, his firm is at full throttle internationally: Asia, the Caribbean, South America, the Middle East. The first divots are still relatively fresh on such heralded designs as Hogs Head, on the headlands of southwest Ireland, and Hoiana Shores, a tropical links in Vietnam. Growing the game is not a novel concept to a man who has been globe-trotting for most of his life.

“Some people join the Army to see the world. I became a golf architect,” Jones says. “I have always been an adventurer.”

Still, he concedes, “I’d also like to be doing more work in my own country.”

That’s easier said than done. Course design is not immune to fashion, and other leading names now walk the runaway. The work of staying relevant is never-ending. Jones is unabashedly competitive. It rankles him to lose out on a bid, just as it irks him to see his father’s work erased, as has happened with recent marquee restorations, including Baltusrol, Congressional and Oakland Hills.

Proud and protective of his family legacy, Jones is also keen to safeguard it for the future. That means pushing forward with his own work while pushing back against the notion that the era when the Joneses reigned supreme was the era when golf somehow began to get it wrong.

“There’s a romanticized idea of the so-called Golden Age, and it bothers me, in part, because it suggests that nothing worthy has come since,” Jones says. “If that was the Golden Age, we must have had a Platinum Age after, because we’ve had a great variety of responses from architects like Fazio, Nicklaus my brother and my father. I’d also add myself to that list.”

Jones’ first blush with the game, in his hometown of Montclair, New Jersey, predates his earliest memories. A family story goes that when his mother, Ione, handed Bobby a rattle in his crib, his father stepped in to make sure he was holding it with a proper grip.

Bobby grasped the fundamentals well enough to lead his Montclair high school team to a state title. Not long after, he helped his team at Yale capture the Eastern Intercollegiate Championship. Along the way, he took lessons from the Tour great Tommy Armour and triumphed as a member of the 1956 U.S Junior golf team in its matches against Scotland. But turning pro was never in his plans.

Having interned for a U.S. senator during a summer break in college, Jones pictured a life in politics, which, he says, meant “learning the secret language of the law,” which meant law school.

One year of that at Stanford was enough to teach him that working with his dad was a better idea. The world’s most famous architect soon had a West Coast office, headed by his firstborn son.

It was the early 1960s, and Jones Sr. was at the height of his powers, but he couldn’t be everywhere at once. Bobby was willing to go anywhere. Many of his trips were to Southeast Asia, a frontier ripe with business opportunities. Other stops were closer to home and offered a high-profile, hands-on education. As his father’s point man at Spyglass, in Monterey, and Mauna Kea, on the Big Island, Bobby got a crash course in the trade.

The more he learned, the less he hesitated to challenge his mentor on everything from budgeting to bunkering. Junior and Senior’s clashing views led to open disagreement the first time Bobby took the lead on a design, at Silverado Country Club in Napa. The South Course, which opened in 1967, was not so much a monster as it was a playful Lab, fun and engaging with gettable greens that contrasted with the pushed-up targets Bobby’s father favored.

“It dawned on me after playing it that I had designed it for my own game,” says Bobby, a relatively short knocker with a deadeye touch. He had also designed it for resort guests. The client loved it. If Jones Sr. was somewhat less enchanted, it hardly mattered. Within another five years, Bobby was running his own show Armchair Freudians have had a field day analyzing Jones family dynamics, which have not always been smooth. But as Bobby describes it, his departure from the mother ship was carefully planned and his father accepted it with equanimity.

“ ‘As birds grow up, they have to fly’ was his direct quote to me,” Bobby says.

Helming his own firm, Jones gained a reputation for adaptability and inventiveness. Many of his projects presaged contemporary currents. At the Links at Spanish Bay and Chambers Bay, both of which restored native landscapes to blighted coastal sites and stitched public hiking trails into their designs, Jones championed eco-consciousness and mixed-use access before the industry fully awakened to their importance. More recently, his open-mindedness was key to landing jobs at SentryWorld, where he welcomed the chance to tweak his own creation, and at Hogs Head, whose owners wanted a whimsical course that mingled classic features with an unconventional number of par 3s and par 5s.

“We didn’t want an architect who was going to tell us, ‘You’re the guys with the money, but I’m the creative genius, so leave me be,’ ” says Hogs Head codeveloper Bryan Marsal. “We wanted it to be collaborative. And we had very specific criteria. Bobby met them all beautifully, while showing plenty of his own creative genius too.”

Jones is a member of the R&A, Pine Valley and San Francisco Golf Club, but he might be most at home at the Bohemian Grove, an artsy retreat tucked into the redwoods of Sonoma County that courses with blue bloodlines and big bankrolls. His other happy place is Hanalei, on the north shore of Kauai, where he and his wife, Claiborne, honeymooned six decades ago and where he has owned a home for nearly as long. Hanalei is also where Jones built the 27-hole Princeville Makai Golf Course, which was started with his father but became the first job he completed on his own. Upon Princeville’s 1972 opening, the faved sportswriter Dan Jenkins hailed it as “the most enthralling” course he had ever seen—influential praise that helped announce Bobby as his own man.

In March 2020, Jones was on Kauai with family when the world shut down. He spent the next year-plus of the pandemic stranded in paradise, passing the time swimming, writing poetry and playing golf with other castaways, including his friend, actor Pierce Brosnan. Brosnan, who describes Jones as “a Gandalf figure traveling the world and designing courses of alchemy and beauty,” says he stopped counting the times when other golfers approached, asking Bobby for an autograph without seeking the same from a man who played James Bond.

“I would simply stand by with a gleam in my eye,” Brosnan says.

Few people in any setting have spent time with Jones without being treated (or subjected, as some of his close friends put it playfully) to impromptu poetry readings. Jones, who is active in several organizations aimed at fighting climate change, often writes about the natural world. He talks a lot about it too. One of his gripes with the current course restoration craze is its emphasis on tree removal, which he says often strays into artless clear-cutting, with costs all around.

“Trees provide shade, they can enhance strategy and they are carbon sinks,” Jones says. “If anything, plant more of them.”

His other quibbles are strictly architectural. His father’s mantra was “hard par, easy bogey.” Recent updates of his father’s work, Bobby believes, have pretty much turned that thinking on its head.

“Now, it’s become easy par, hard bogey, and not for the better,” Jones says.

He could go on. It’s a big topic. But the issues often boil down to what Jones believes are misconceptions about his father. “You want to talk about using the land, allowing for the ground game, encouraging options?” he says. “Look at my dad’s work at Peachtree and Spyglass or the changes he made at Augusta. My dad could play the white keys and the black keys. He could do jazz and he could do classical. He could do it all.”

At CordeValle, the sun is slanting low over the hills, and Jones is strolling the grounds around the clubhouse. The course is semiprivate, with tee times for resort guests and accommodations that include three bungalows named after fabled architects and fronted by statues of their likeness. One of the bungalows pays homage to Alister MacKenzie, another is a tribute to A.W. Tillinghast. Jones strides past them both before arriving at the third: the Jones bungalow. Flanking its entrance are side-by-side bronze busts of Bobby and his father. Though there’s no mistaking one for the other, the family resemblance is plain as day.